MilitiaWatch was given files from the internal and semi-public communications of a Georgia-based militia group. These files, provided to MilitiaWatch by the Atlanta Antifascists, show extremely worrying plans that may be indicative of conversations within other contemporary militia groups. This piece assesses some of this content and provides context that may be useful to those looking to assess the psychic and social environments in which militias like this seek to engage.

This is a longer post, so there is another TL;DR on the piece, which can be read here for the top notes:

There exists among the militia milieu several diverging notions about what the role of the militia may be. To some, it’s an insurrectionary force aimed at keeping “tyranny” in check. Others contend that the “militia” is simply any armed citizen of fighting age to be activated in times of emergency. Others still argue that the “militia” is a defensive force to stop outsiders from attacking their own personal territories. Finally, another dominant view is that the “militia” is a counter-revolutionary force deployed to defend the current order.

It is extremely common that militia groups will claim to be one representation of the “militia” in public while expressing a different representation amongst themselves. It’s also quite common that these distinctions are almost more psychic or individualized, as a militia gathering can come to represent different things to different members, who will often cherry-pick the representation that they believe is most righteous.

In times where conservatives and far-right activists feel most besieged, militia groups may start calling themselves ‘revolutionary patriots’ set at stopping ‘tyranny’ or ‘socialism’. These conditions are usually those anecdotally most associated with violence against actors that militia members view as political adversaries – be they ‘BLM’ or ‘antifa’ or ‘RINOs’, or something else altogether.

One of the important recent developments in militia self-framing and self-identification, though, is the notion of the “Home Guard”, a posturing that militia activists (leader and membership alike) claim as purely defensive in nature. This notion is not new, nor is it unique to militia activists. Fascist groups, including recent reprisals like Patriot Front, opt to carry shields for the optics that they are carrying defensive tools, a claim that is counteracted when said activists then use said shields to bludgeon their foes. The Boogaloo movement and sovereign citizen movements (and others too) individualize this as they voice common refrains of “I just wanted to be left alone” to justify offensive violence as revenge for government overstep.

This article will look at the “Georgia Home Guard”, a militia gathering based in Ellijay, Georgia, that has been training to create a compound since J6. Before getting into the militia, though, there are some important ideas surrounding the group’s name and the militia milieu they find themselves within.

A history of “Home Guard” nomenclature

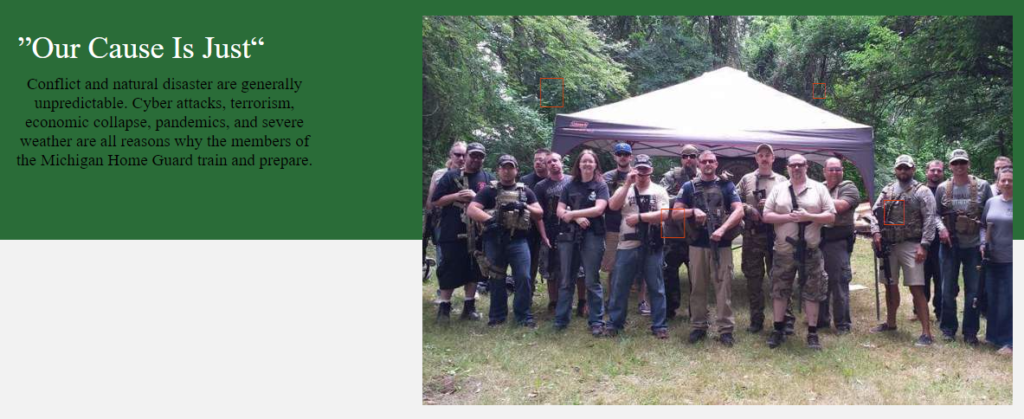

The “Georgia Home Guard” is not the first militia to use the name “Home Guard”; the arrestees in the Michigan governor kidnapping conspiracy were socially connected to a series of militias, of which one is the Michigan Home Guard. The Michigan Home Guard, which formed in late 2014, uses as a logo a picture of an 18th-century minuteman with a musket in the olive tones common to militia patches:

The Michigan Home Guard claims to be a “homeland defense force” and has a banner on one of their sites literally reading “Our Cause Is Just”, listing “pandemics” as a reason they train. An important note: the Michigan Home Guard has been involved in anti-lockdown demonstrations, including some attended by Wolverine Watchmen. Guns feature quite heavily in many of the group’s representations of themselves.

There are other contemporary militia groups calling themselves a “Home Guard” this includes the “Ohio Defense Force Home Guard” (cited in 2016 SPLC active groups report). It also includes the now-defunct Confederate States Home Guard (cited in 2010 SPLC active groups report), which had chapters in 18 states, including non-Confederacy states Alaska, California, Iowa, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin (around 55% of all chapters).

The history of the “Home Guard” in the United States is essentially just the history of the 19th-century militia itself, as militia groups throughout history have claimed a community defense model regardless of their involvement in offensive actions. But the contemporary United States isn’t the only place with a history of Home Guards.

In the UK, a citizen militia called the “Local Defense Volunteers” (LDV) would become renamed the “Home Guard” and were only active during WWII, operating 1940-1944 across local volunteers numbering 1.5 million. It excluded those already working as police or other armed forces. One of the primary targets of the Home Guard in the UK was that of “fifth columnists”, traitors to the national cause. Ironically, the term’s origins are likely derived from the Spanish Civil War, where fascist leader Franco apparently described a “fifth column” of nationalists ready to attack Madrid from the inside to aid the four military columns en route to the city (e.g. the “quinta columna” would rise up and act as nationalist auxiliaries). The UK-based “Home Guard” would be disbanded 8 months after the surrender of the Nazis. The Northern Ireland-based contingent of the Home Guard, known as the “Ulster Defence Volunteers” or “Ulster Home Guard” was formed specifically from members of the occupying Ulster Special Constabulary “known as the ‘B’ Specials by many locals” after fears were raised that the militia might end up accidentally training Irish republicans. This led to the Ulster Home Guard having in 1942 a total of 150 Catholics among a force of around 40,000 (see also this book by Robert Fisk).

Other “Home Guard” gatherings have sought to continue imperial rule. In late 1946, while a major push for Indian independence was underway, an Indian “Home Guards” volunteer force was created to quell riots. The Indian Home Guards were clearly unsuccessful, as Indian independence from the British followed just a few months later in 1947. In Kenya, a loyalist “Kikuyu Home Guard” was formed in 1953 as a paramilitary force to combat the Mau Mau Uprising. The Kikuyu Home Guard was also named after the British Home Guard and was quite controversial among the Kikuyu people, despite the imperial authorities attempting to make the Home Guard look Kikuyu-led. Unlike the Indian Home Guard, the Kikuyu Home Guard was successful in their brutal repression of the Mau Mau insurgency, taking responsibility for around 40% of all Mau Mau deaths during the 8-year war.

There have been numerous other “Home Guard” gatherings throughout the world, including an Australian one created in the image of the UK Home Guard, the Danish “Hjemmeværnet” that still operates today with corresponding sub-organizations for each Danish military branch, and the Norweigian “Heimevernet” that is similar to the Danish force and has 40,000 members, and the Swedish “Hemvärnet” formed during World War II out of former militia groups.

Several other “Home Guards” throughout history were established specifically to explicitly fight for fascism or against communism. These include the Estonian “Omakaitse” was founded in 1917 to fight against the Soviets on behalf of the Nazis, the Sri Lanka Civil Security Force founded in 1985 out of a bill that brought all Home Guard militias under the authority of the police against a communist insurgency, the Slovenian “Slovensko domobranstvo” that operated as an anti-Partisan armed force as part of the Italian-supported “Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia”.

The US Civil War also included two “Home Guard” corps, one for each side of the conflict. Both the “Confederate Home Guard” and its Union equivalent were formed out of local militias created from sympathetic locals. The Confederate Home Guard worked as auxiliaries to the Confederate Army and also tracked down deserters to collect bounties. By the war’s end, all Confederate states had a Home Guard. In contrast, the Union equivalent established a Home Guard corps in 4 states (Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, and Western Virginia) and mustered regiments from among five native tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole) that the colonial state considered “civilized”.

All this to say that there’s a long history of formalized “Home Guard” corps, usually organized above a district level and usually oriented towards conservative, colonial, or anti-communist causes. In most cases, these groups fought within their own territory but operated explicitly or under thinly-veiled paramilitary justifications – assisting the military of the state from which they were mustered and with the blessing of the national security apparatus.

Georgia’s “Home Guard”

Now we will get into the Georgia Home Guard, which meets many of the ideological characteristics of these historical “Home Guards” but operates as a right-wing militia outside of the structure of the US state.

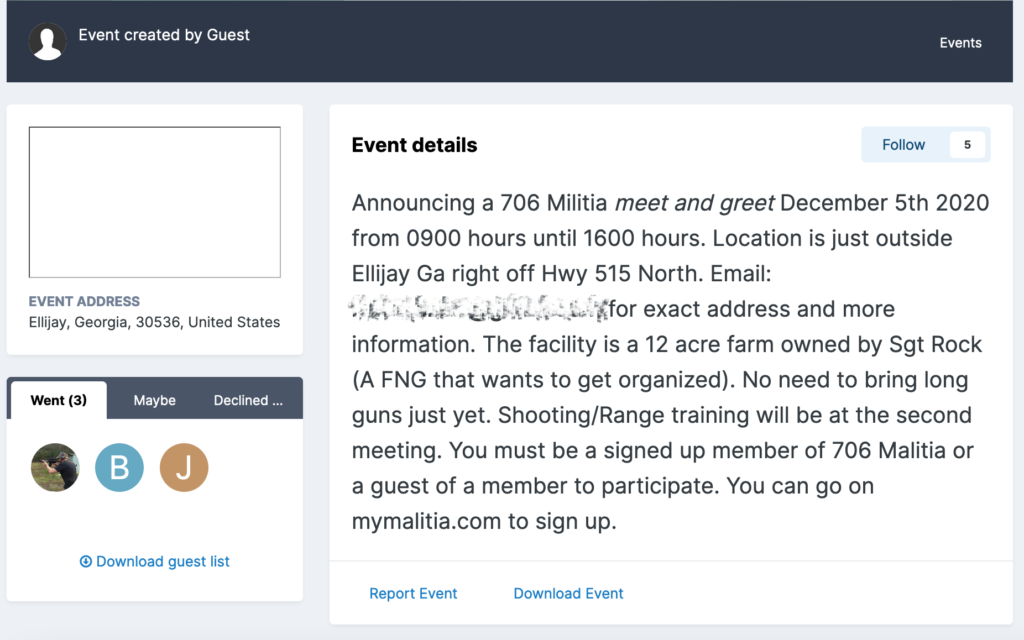

The Georgia Home Guard was established in 2020. It was created by Jay “Bushrod” Johnson, the group’s de jure leader, but is run by Richard “Sgt Rock” Haskins. The militia group did not start out with the name “Georgia Home Guard”, but is instead an outgrowth of the “706 Militia”, an area code militia created on MyMilitia, a blog that allows militants to shop for a militia group. The group is centered around Ellijay, Georgia, a community about 1.5 hours north of Atlanta by car.

Johnson, who also goes by “Commander” engages in very little communication among the group, but used to create the group’s events on MyMiltia. In one such post from December 2020, Haskins (Sgt Rock) is described by a site ‘guest’ (ostensibly Johnson) as an “FNG” (or “Fucking New Guy”).

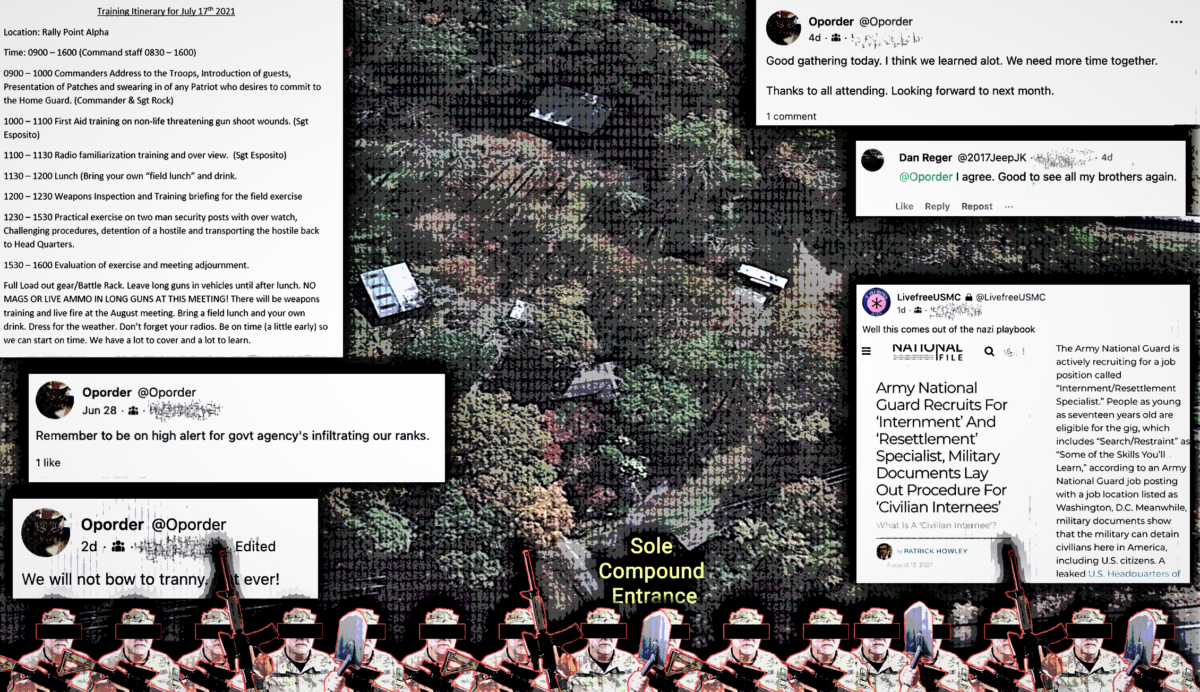

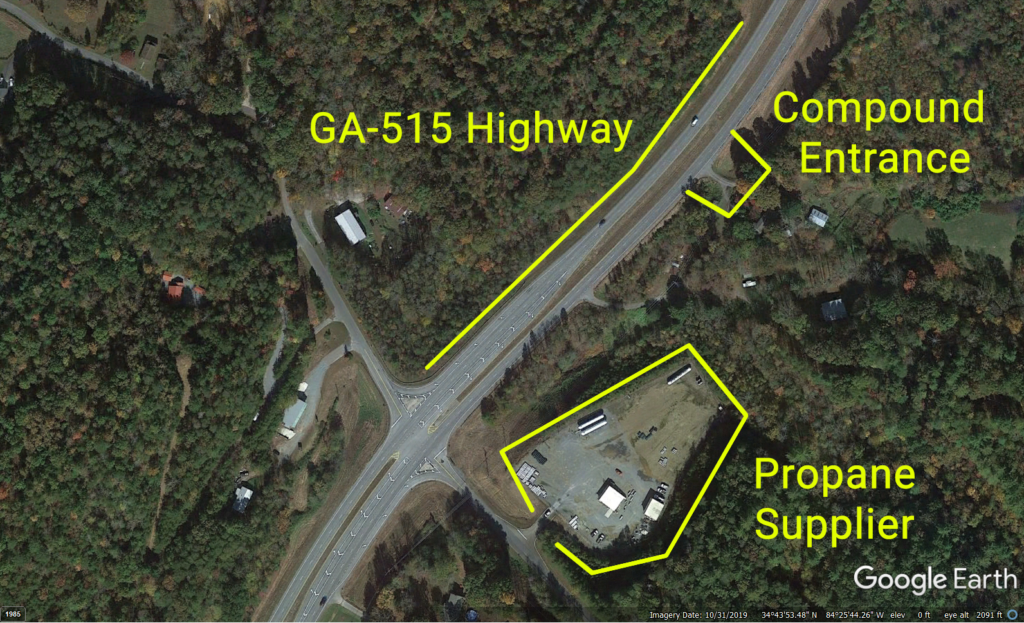

Haskins lives off Georgia Highway 515 and has established his primary residence as “Rally Point Alpha” or the “Colony” in internal communications leaked to MiltiaWatch by Atlanta Antifascists. The Colony effort is intimately connected to the full operations of the Georgia Home Guard, for which Haskins constantly pushes members and their families to commit to joining his survivalist project. The Colony is located on a long, slim lot with only one point of entry off the highway.

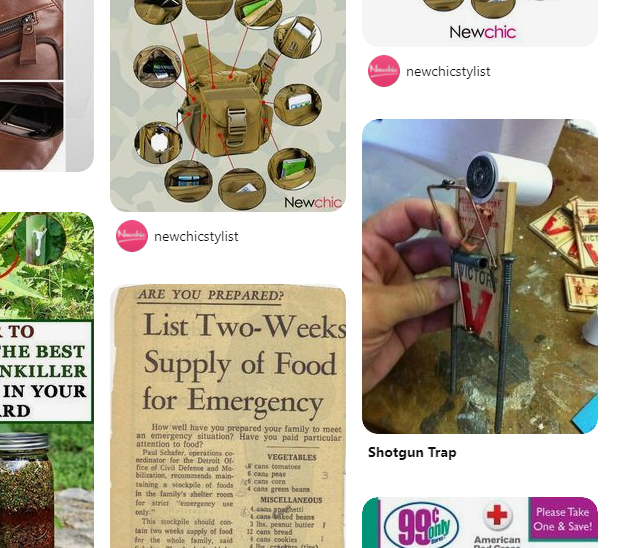

In attempting to convert this militia into a compound-bound prepper community on his own property, Haskins has pushed new recruits to agree to fill specific roles within the community. Haskins pushed Johnson, for example, to fulfill the role of “EOD” (“EOD” refers to “Explosives Ordinance Disposal” within the US military). Johnson’s enthusiastic reply is quite telling of the group’s orientation. The “Commander” replied that he would be willing to act as the “demolition person, improvised explosive guy, booby traps, and whatever tactics we need to slow, channelize, and eliminate the foes that threaten the ALPHA site.” On a Pinterest page likely belonging to Johnson, the user pinned under the board “Big Out Bags” (probably “Bug Out Bags”) an image of an improvised shotgun shell trap triggered by a mousetrap and placed into the ground, titled “Shotgun Trap”.

It is yet unclear if Johnson, Haskins, or their crew have followed through to place IEDs and other dangerous traps on Haskin’s property. This notion is quite worrying, though, as the proposed compound is off of a 4-lane highway and the entrance to the property is within 150 yards of a propane supplier that shares a property line with Haskins.

In joining the compound, members of the Georgia Home Guard are required to sign a liability waiver form, which has Haskins’ rather than Johnson’s name on it. The property on which the Colony is set was bought by Haskins in 2016 and he claims that his interest in building the Colony predates the establishment of the Georgia Home Guard in 2020. It’s therefore quite likely that in the last five years, Haskins has been working up towards this moment at the Colony, wherein he and his comrades are encouraging militia members and their families to integrate themselves into the Colony.

Another key actor within the Georgia Home Guard ecosystem is De “Oporder” Wood, who is officially in charge of the militia’s recruiting efforts and therefore runs the group’s Gab group. Wood is a veteran of the US Army who claims to have fought in Vietnam. With the Georgia Home Guard, he has volunteered for several seemingly disparate roles at the group’s Colony: carpenter, firefighter, handyman, power engineer, and ranger master assistant. Wood, who is ranked “Master Sergeant” within the group, also posts content on the Gab group about militia procedure and preparedness.

Among these posts by Wood are videos from Ford Fischer of Chris Hill’s III% Security Force training, with the disparaging caption, “There are ways to train. This isn’t one of them.”:

These posts on Gab are likely part of what militia members are tested on when attempting to join the group and are therefore perhaps more useful to new recruits joining the Georgia Home Guard than as recruitment material itself.

The Georgia Home Guard appears to follow a familiar recruitment and integration protocol for joining the militia. There are, of course, some inconsistencies and redundancies, too. It seems like most of the group’s recruitment isn’t through Gab, a site dominated by neo-Nazis and Christian identitarians, but instead comes through MyMilitia. MyMilitia is Haskins’ domain, despite Wood bearing the responsibility to recruit new members.

After a recruit reaches out for information, Haskins asks the would-be recruit three questions, which are adapted to the user:

- What is your citizen status?

- Can you legally possess a firearm?

- Are you a veteran or a first responder?

Haskins then tells recruits to join the group’s Gab group (awkwardly by giving a search term instead of a URL) to get vetted by Wood. Without verifying that the Gab vetting is complete, Haskins sends a copy-paste explainer/advert for the group, repeating a lot of the same content and questions as previously and saying that the group “[operates a] colony and train[s] under military protocol.” The Gab detour obviously leads to confusion and makes the group’s Gab page a redundant point for the group’s recruitment efforts. Here is a chart of the process:

Recruitment is clearly a focus for the militia group. In an After-Action Report document for the 17 July 2021 training by the group at the Colony, Haskins wrote, “Recruiting was discussed and was established as our #1 priority.” He went on to say that their online membership needed to grow to “show our strength which will help improve our recruiting efforts”. This isn’t unusual of militia groups aiming to recruit via Josh Ellis’ MyMilitia website, as group member numbers and activity rate appear to play a major role in driving new recruits off-site. In the same paragraph of the After-Action Report, Haskins commends Woods for his efforts running the group’s redundant Gab page.

Recruitment is an obvious interest of the group because at the time of writing, the group’s Gab group has 11 members. This doesn’t mean that they are irrelevant or not to be taken seriously. Atomwaffen, the neo-Nazi group responsible for at least 5 murders in the US, had a total membership of under two dozen, including on a small Discord server of around the same size. The Gab group’s size, however, grew in the last month from 5 members in July to today’s 11. There are at least 16 identifiable members of the militia and its associated Colony.

Notable within Haskins’ copy-paste recruitment text sent to would-be joiners on MyMilitia is the claim “We go by the name of the ‘Home Guard’. No we are not a militia! We are always in a defensive posture.” The defensive posture notion is perhaps challenged by some of the training that the group conducts (in addition to the potential for indiscriminate or accidental harm their IED program might entail).

The group trains monthly, usually around the middle of the month. “Sgt” Jordan Esposito, who has occasionally used the alias “Wraith”, runs a good portion of their training, especially the medical and logistics training. This type of militia training isn’t particularly special to the Georgia Home Guard, as many militias and prepper groups train in both.

However, the Georgia Home Guard’s 17 July 2021 gathering involved training that involved a mock kidnapping drill, described in an itinerary as “detention of a hostile and transporting [them] to Head Quarters”. Kidnapping an imagined enemy is hardly a defensive posture and is made even more worrying by the slew of conspiracy theories to which members of the group often adhere. Theories of this type mixed with easy access to lethal technology and a justifying social sphere can lead to cells or individuals from among their ranks to ‘take matters into their own hands’ and lash out beyond the Colony. The week of the time of this writing, Haskins has been posting on the group’s Gab tactics for how to raid buildings, as well.

Within the discussion of the training in the 17 July 2021 After-Action Report mentioned above, Haskins also added that the “current government is attempting to take total control of the people of this country”, a phrase that is likely directly linked to his mid-August Gab post that “we train and prepare for when [SHTF]. [Well] the s is htf.” This SHTF post refers to when “shit hits the fan”, a phrase popular in militia and prepper circles to represent the end of the order and the beginning of a chaotic and kinetic environment. Within the same day as his SHTF post, Haskins made it obvious the targets of violence when ‘SHTF’, writing: “The Declaration of Independence tells us, when a govt becomes to[o] tyrannical, we have every right to replace it. That time is now.” This insurrectionary notion, particularly coming from the de facto leader of the Home Guard belies the deception inherent in the group’s name. Not only are they training for obviously offensive operations and discussing building IEDs that could injure passersby, but they’re also doing major ideological work to prime their membership for combat and taking the fight to their enemies.

This seems to have been a new paranoia setting in among the militia’s members, who in turn reify the worldview that the government and their enemies are coming to get them. Numerous ominous messages are being sent around among their group, as even non-leadership members are now repeating messages that “The time has truly come.”, phrasing that could be interpreted as a call-to-arms among the primed membership of the Georgia Home Guard.

Another event’s After-Action Report, following a 21 August 2021 gathering at the Colony, detailed that involvement in the militia is highly variable, though. While the AAR includes the note that “Patriot Mike Walker” donated and installed two gun cabinets at the Colony, it also bemoans low participation at August’s monthly Home Guard gathering, leading with the sentence, “I am disappointed to report that only two Patriots showed up for the meeting.” This also does not set the Georgia Home Guard apart from multiple other militia groups analyzed by MilitiaWatch, as waning interest and frustrations of leadership have been a staple of a militia’s lifecycle and indeed its eventual demobilization. Time will tell if leadership’s citing of the lack of members remaining “loyal to that commitment” that they made to the militia will lead to demobilization or a schism among their ranks.

Ending note

The Georgia Home Guard serves as a case and warning for several key dynamics within the militia milieu. First, they represent the propaganda inherent in naming conventions and the burgeoning “we are not a militia” talking point that’s been popular among groups in the wake of J6. Secondly, they display how a claim to a “defensive posture” stands at odds with the situations they plan for internally and how they talk amongst themselves. Thirdly, they indicate that long-term recruitment avenues that have been well-known and well-documented continue to serve militia groups looking to drive recruits into their fold, regardless of the impacts of social media bans. Finally, they show a troubling fascination with wanton disregard for the safety and rights of their political adversaries, a cohort of actors and institutions as broad as they are undefined.

Edit 27 August 2021: Fixed a misspelling related to the “Kikuyu Home Guard” and other instances of the Kenyan ethnic group.